- Home

- Gautam Sen

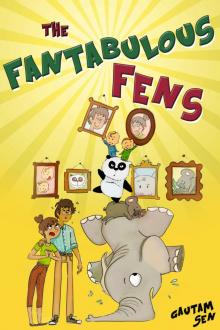

The Fantabulous Fens Page 3

The Fantabulous Fens Read online

Page 3

By now Father Fen had begun to feel a little bad. He threw in the towel. “Let’s tell him,” he suggested.

“Yes, let’s do.” Mother Fen agreed. “Well, Panchu, it’s like this: someone threw something at our house and broke a window glass.”

“A stone?” Panchu asked.

“Probably. Maybe some drunk,” Father Fen put in. “Drunk people are always a nuisance.”

“Or maybe not drunk. It’s because of us — we are not like the others. That’s why we don’t go to school; that’s why teachers come to teach us at home. Isn’t it, Papa?”

“And that’s why we must see to it that we are always together, always one, always willing to help one another, to make up quickly if we happen to quarrel,” Father Fen explained almost in a whisper; but there was a lot of feeling in his tone.

“I have great brothers!” Panchu declared proudly.

“And we have great sons!” Mother Fen and Father Fen declared together, equally proudly.

“And we have a great Ma and a great Papa!” Panchu finished off.

It was so late at night now that they began to feel sleepy. After Father Fen had cuddled Panchu for a while, he was lowered onto his mo-bike, on which he rode off, waving to them, to his little room; and then Mother Fen and Father Fen took themselves to bed.

The next night again stones were thrown at their house, but this time it was not glass that the stones struck, but wood; and when one day Father Fen dropped in to buy a few groceries at a nearby departmental store, he overheard one customer whisper to another, “That man to your right — the one in a white shirt — I’ve heard he and his wife are black magicians.”

4 - Why the Fen Children Didn’t Go to School

Panchu and Pinchu were so small in size that Mother Fen and Father Fen could never even think of putting them into school. Koala too was small, but he was not so small that he could not be sent to school, and Baby Panda and Mumbo were stalwart children — though Baby Panda was very soft — who were rather larger in size than other children of their age.

At first, just as an experiment, Mother Fen and Father Fen wanted to send Koala, Baby Panda and Mumbo to school to see if this would work out. They had some doubts, of course, because when you are different from the rest, others often make life difficult for you. But, the way Mother Fen and Father Fen looked at it, sooner or later their children would have to get used to be treated differently. How long could they be protected in the Fen home? One day they would have to face the world, and if they left this training for too late, they would find it difficult, if not impossible, to adjust. That would be very sad, wouldn’t it? If they went to school, certainly there would be a lot of noise about them the first few days. That was only to be expected. Maybe some children would call them names; maybe others would make fun of them. But it was perfectly possible that many would love them too, both teachers and students. Once people got used to them, they would be treated just like everybody else, and in that way the three children would learn to take their place in the world.

The trouble was, they were just not three, they were five. They had always been together, the best of brothers to one another, and to separate them suddenly would be heartless, wouldn’t it? How would it affect the minds of Pinchu and Panchu if only they were kept at home and the other three were sent to school? Besides, Mother Fen and Father Fen reasoned out, they would have to get special tutors for Panchu and Pinchu anyway, tutors who would teach them at home. If that was the case, the same tutors could teach all five of them — it would put more fun and enjoyment into their learning and, if anything, it would add a new flavour to their relationship with one another. So it was finally decided that the Fen children would receive all their education at home.

Monday was the busiest day for studying. It was the day for languages. The Fen children learnt two languages: Khushi, which was their mother-tongue, and English, because it was something of a universal language. Tuesdays they learnt Mathematics, Wednesdays Science, Thursdays History, and Fridays Geography. There was a separate tutor who taught them each of these subjects for one hour every week, so that the Fen children altogether had seven tutors. Naturally they all had to be paid, and Father Fen worked very, very hard indeed to earn more than he had been earning earlier, before the children were born; but he loved his children so much that this extra hard work came easily to him — it was what they call a labour of love — and he never regretted it or felt sorry for himself because of it.

The education the Fen children got at home was a little different from the education they would have got at school. As you now know, except on Monday they were taught only one subject a day, and even that subject was taught differently from the way it is usually taught in schools. Let us take an example. Say they were doing a lesson in history, learning about Alexander the Great’s invasion of India, and his encounter with Porus. Porus was a king in northern India. When Alexander defeated him in battle, Porus was brought before him.

“How do you wish to be treated?” Alexander proudly asked him. Though Porus had lost the battle, he had not lost his courage or his dignity.

“As a king should treat a king,” he answered.

Alexander was so impressed that he returned Porus his kingdom in return for a tribute which Porus would have to pay from then on. Now, when the Fen children heard this story, they did not just sit back and listen; for, after listening, they acted out the scene: they became Alexander and Porus and the other soldiers. Then they talked about what this showed about the characters of Alexander and Porus. Then they drew their pictures; they drew the horses and the elephants and the battlefield; and they coloured all the people and the animals and the things, and before they knew it, more than an hour had passed — it was one-and-a-half hours, and Miss — for they had a woman for a history teacher — suddenly jumped up and said,

“My! I didn’t realize it was so late — I better be going!”

But even after she left, the children sat at their desks and carried on with their colouring. So, as you can see, learning was great fun for the Fen children. No wonder they had their classes in their play-room, though, of course, once they had finished, they had to fold up their chairs and desks and put them into a corner.

5 - A Lesson on Show White

Their English teacher was Miss Priya. She was sixty-five years old, and she had been teaching English all her life. She had retired from her last job and was therefore free to come to Fens’ Den at 10:00 am, when all the working teachers were busy teaching in school; but though she was sixty-five years old, she went around as if she was forty or forty-five. She had undergone plastic surgery to remove the creases on her skin, and her hair was blacker and thicker than it had been thirty years ago. That is because she wore a wig. Of course, she pretended she did not wear a wig, and she told no one about her plastic surgery. Though she could fool most people about her age, there was one place where she could not do this — that was the school where she had worked; where, before being given her job, she had had to submit this certificate and that certificate (like they do everywhere), and in some of these her actual date of birth was recorded. So, after retirement, Miss Priya had to rest content with telling others that she had given up her job because she prized her freedom, and because doing any kind of job made one a slave. She also pretended there was no shortage of money in her life (she thought people would look up to her for this) and therefore there was no need for her to work full-time for money. In spite of all this, it must be said that Miss Priya was not at all a bad teacher, and she was rather fond of children. Like many teachers, she did not force children to learn up lessons by heart; and unlike many teachers, she let her pupils ask her whatever questions came to their minds.

One day she did the famous story of Snow White and the seven dwarfs with the Fen children. First they read about how a certain Queen wished for a daughter as white as snow, and how this wish was granted. Because Baby Panda himself was mostly as white as snow, the Fen children imagined a girl who

would look somewhat like him. That was quite all right and understandable. What Baby Panda himself could not understand, though, was why the Queen was so particular about the colour white, when black was clearly as beautiful. Weren’t Mumbo and Koala black, and weren’t they as handsome as handsome could be? Baby Panda asked Miss Priya about this. Miss Priya, who used skin-whitening creams, was a little taken aback by the question, but she was an experienced teacher, and she knew how to deal with the situation.

“Well, we all have our likes and dislikes, don’t we? Someone’s favourite colour is red, another’s is blue, a third person’s is yellow — you see?”

Baby Panda understood, and they continued. They came to the part of the story where Snow White’s Queen step-mother put on one disguise after another and succeeded in trapping Snow White again and again in the forest cottage of the seven dwarfs. Though the kind dwarfs who gave her shelter kept warning Snow White that she should not let anyone into the cottage in their absence, the evil Queen always managed to make her way in by tempting Snow White and making a fool of her. Koala wondered aloud why Snow White didn’t listen to the dwarfs, who were older than her and wanted her good, and Pinchu asked whether Snow White wasn’t very clever, because in spite of the warning of the dwarfs, she didn’t seem to ever learn. Panchu said it would have been better for Snow White’s mother to have wished for a girl who was clever rather than beautiful.

All this made Miss Priya gulp. She had done the story of Snow White with dozens of children, and there was no one who had not considered it absolutely wonderful. Though the Fen children seemed to be enjoying the story all right, their reactions came as a rude surprise to Miss Priya. It kind of dampened her enthusiasm, but she carried on bravely with the rest of the tale. They came towards the end, where Snow White is being carried in a glass coffin, and the bumps on the path make the poisoned half of the apple stuck in her throat shoot out, so that suddenly she sits up alive and everyone is very, very happy indeed.

Mumbo started laughing (you know what a laugh he has!), as much because he was as happy as anyone else that Snow White had revived as because he found it quite funny that any poison should work in that way.

“Why are you laughing, Mumbo?” Miss Priya wanted to know, with a frown on her brow.

“Miss, if the poison was only in the apple and not also in her body, how did Snow White die in the first place?”

“Didn’t she chew her food, Miss?” Pinchu enquired.

“The poison was in the apple, and the apple was in Snow White; so the poison was in Snow White as well — that’s why she died,” Panchu remarked with a twinkle in his eye.

Miss Priya was hurt. Normally she did not show her feelings when she was hurt, but now you just had to take one look at her to know that she was feeling rather upset.

“When you say all these things, children, it takes the fun out of the story, don’t you see?”

But the children didn’t see. They thought there was a lot of fun in the story, and they were glad they had heard it. Only, some questions had come to their minds automatically, and they had wanted to clear their doubts. They felt sad, too, that Miss Priya had felt hurt.

Together they said, “Sorry Miss, we enjoyed the story very much, we really did!”

6 - Miracle Evening

They had invited their neighbours, the Superstitions, to high tea. The Superstitions had said no straightaway, and that had been quite a jolt to the Fens. But half-an-hour later Mrs. Superstition got down to reading the week’s fortune forecast in the ‘What The Stars Foretell’ column of a popular magazine. Under her zodiac sign a line read, “Do be nice to strangers you meet, because this will work out to your benefit.” Through a servant she immediately sent a message to the Fens saying that they would be most happy to drop in the next evening at five o’clock. That was the time they had been invited. Mother Fen and Father Fen wondered what had made the Superstitions change their mind, but they were happy anyway that they were coming.

The two sons of the Superstitions were called Bojo and Dojo — Bojo was the elder, and Dojo the younger. That evening, when the Superstitions came into the house of the Fens, Baby Panda was in the front room, bouncing the big white plastic ball which looked like his younger brother. Actually he had been playing in another room, but the ball had bounced this way and that and finally brought him to that front room. When the bell rang, it was Mother Fen who answered it, but no sooner had she opened the door and said, “Hello! Come in, come in!” than Jojo’s face lit up with uncontrollable excitement.

He stepped in, pointed a finger at Baby Panda, and shouted, “Doll, doll! What a big doll! A walking doll! A playing doll! Must be from America!”

Baby Panda stared hard at him and said, in his sweet tone, “I’m not a doll — I’m Baby Panda. I’m not from America, I’m from here!”

“It can talk too!” Jojo clapped. “Ma, I want this doll!” and to find out more about the doll he poked Baby Panda.

Baby Panda tried to side-step away from Jojo, but Jojo being faster than him this was not only difficult but quite impossible, so that Baby Panda was left with hardly any choice but to push Jojo away the next time he tried to poke him. Now Baby Panda was a healthy child, and stronger than most other children in spite of his cuddly looks. His push, even when it was given without any special effort, was some push – it sent Jojo hurtling backwards as if he had suddenly walked into a tornado. His mother was perhaps three feet behind him, and it was against her large stomach, which stuck out like a pumpkin, that he went and dashed his head. His mother screamed and lifted her arms and quickly went back, where her husband and Jojo’s father happened to be moving forward. Unlike his fat wife, he was a thin, slight man, and the force and suddenness with which his wife struck his body did not do his balance any good. He collapsed and crumbled to the ground, and sat there gazing about him in an absolute daze.

“What’s this?” Jojo’s mother screamed, as much in anger as in fear, “I’d been told to be careful, but I’d no idea it would be this dangerous. If I’d known there were animals running around free in this house, do you think I’d have ever come? Why don’t you put him in chains? Anything could have happened to my poor Jojo — isn’t he lucky he’s alive!”

Mother Fen defended her son by saying, “It wasn’t Baby Panda’s fault at all — it was your son who was irritating him!”

But Baby Panda was the friendliest of boys — sensing that the situation was getting very, very unpleasant, he broke into a big, big smile, opened up his arms, and took a few bouncy steps towards Jojo with the aim of giving him a friendly hug and making up for whatever had happened. Just at this moment Mumbo entered the room from the door at the back. He had heard some of the noise and had come to see what the matter was. As soon as he realized that Baby Panda was coming to him, Jojo turned and ran to hide behind his mother; in his hurry he failed to notice that his father had dropped to the floor, with the result that he tripped on his father and fell on him like a sack of potatoes.

Glaring at Baby Panda, Mrs. Superstition raised another yell but Bojo, who had been watching the friendliness of Baby Panda’s ways, walked up to him and embraced him like a brother. Mumbo, who found all these goings-on rather funny, began to roar with laughter. Mrs. Superstition, glancing in Mumbo’s direction, repeated her yell and, dragging Jojo up from the floor, where he was on top of his father, pulled her through the front door, screaming “Black magic! Black magic! Better run before they turn you into a beast or whatever!”

“Jojo, Jojo, he’s so nice, just hug him and see!” Bojo called out to his younger brother; but Jojo was in his mother’s grip, and under her influence, and it did not seem at all likely that he would come back. Mr. Superstition, who had gathered himself and scrambled up by now, threw Bojo a flushed look and said, “Okay, come along now!”

“I want to play with him!” Bojo protested.

“You want to see my cricket bat?” Baby Panda asked Bojo. “It’s a special bat — you can bat with both sides.�

�

“You come!” Mr. Superstition commanded Bojo. “Your mother’s gone.”

But Bojo was in no mood to give in. “I want to see his cricket bat,” he insisted.

“Uncle, you want to see my cricket bat? — you can play with both sides,” Baby Panda asked Mr. Superstition, who had a calmer mind than his wife. He remembered the line his wife had told him: ‘Do be nice to strangers you meet because it will work out to your benefit.’ It was clear to him who the strangers were, and it amazed him that his wife could have forgotten all about it so soon. That was the trouble with women, he thought. They were always getting excited … and forgetting the really important things! Besides, cricket had always been his favourite game, but he had never seen a cricket bat both sides of which could be used!

He allowed Baby Panda to lead him to their play-room, with Bojo and Mumbo following. When the four of them had just entered the children’s play-room (where they found Koala rope-climbing), Panchu breezed into the front room on his mo-bike, looking as much like a traffic inspector as it was possible for a young fellow like him to look. Coming to a screeching halt in front of Mother Fen, who was sizing up the situation, he took off his plastic helmet and asked, “What seems to be the problem here, Ma?”

Mother Fen told him. She had just finished speaking when there were excited noises outside and the front door began banging.

“Open up, open up fast!” shouted a pair of rude, unfamiliar voices, followed by the loud wailing of Mrs. Superstition, who was beating her chest and wailing, “My husband and my child are stuck inside! Save them before it’s too late! They’ll work their black magic on them, I tell you! God knows if they are even alive by now!”

Mother Fen’s heart leapt to her throat. She would have called Father Fen, but Father Fen was already there with a ‘what’s going on here?’ look on his face. He had been meditating, and then writing in his study, and had come out for a break.

The Fantabulous Fens

The Fantabulous Fens