- Home

- Gautam Sen

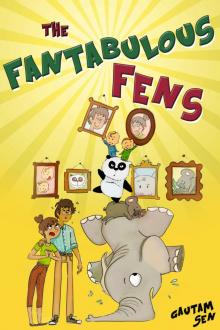

The Fantabulous Fens Page 2

The Fantabulous Fens Read online

Page 2

“I thought I’d drop in yesterday, you know, but then again it struck me I should give you two or three days to settle in.” She looked around with inquisitive and admiring eyes. “Everything’s looking so ship-shape — how on earth did you manage to put everything in order so fast? You must be having a team of servants and helpers!”

“I have some very able children to help me out,” Mrs. Fen replied proudly. This was really an exaggeration, because the child she mostly meant was Mumbo. Mumbo could do loads of work in no time, and that too without too much of a sweat. Pinchu and Panchu and Koala were too small in size to help in carrying things or moving them around — though Panchu did have himself put up on a table, where he stood arms akimbo and issued orders and directions to Mumbo, who found the going much lighter with this live entertainment — and, though Baby Panda was strong, he was too slow and easy-going to be of much help. All he carried were some books, two chairs, and two coffee tables, after which he sat down to rest and fell asleep!

But though the children were not listening right then, Mother Fen did not want to praise only one child and leave out the others, especially before a stranger.

“How lucky you are!” Mrs. Hysteria beamed. “You have many children?”

“Five,” Mrs. Fen answered fondly, but a little guardedly too, because in the past many people had made many odd comments about her children. “Won’t you sit down?” she added, motioning to a sofa.

“If I’m not disturbing you!” Mrs. Hysteria exclaimed gleefully, accepting the offer with great enthusiasm. But that was when it happened.

No sooner had Mrs. Hysteria started to get down to sit on the sofa than she absolutely froze. She was neither fully standing up nor fully sitting down — her knees were bent and her body was thrust slightly forward when she got so stuck in that position that you might have mistaken her for an extraordinary statue had you happened to enter the room. Her eyes were fixed at the curtained entrance to the room from inside the house. There stood Mumbo, his face wreathed in an angelic smile and his palms folded together in the traditional Indian greeting of Namaste. In fact he did say “Namaste, Aunty”, but that was the exact moment that Mrs. Hysteria turned to stone.

Mother Fen took a quick glance at her dear Mumbo and tried to take charge of the situation.

“That’s my son Mumbo”, she announced, hoping that it would somehow help and de-freeze Mrs. Hysteria, but it had only partial effect: Mrs. Hysteria stumbled back, collapsed into the sofa, and passed out.

Thank God for the sofa, for had it not been there, Mrs. Hysteria would have fallen to the ground and hurt herself seriously.

People had reacted in so many strange ways on first seeing her children that Mother Fen was under the impression that she had seen it all. But no one had fainted before like this, and with a little cry of alarm she rushed up to the sofa, at the same time calling out to Mumbo, “Quick — fetch some water, my poppet!”

She normally said “Mumbo”, but now she said ‘poppet’ because she felt that Mumbo might have been hurt at Mrs. Hysteria’s reaction, and she wanted to make up for that.

In a flash Mumbo went in and re-appeared, a mugful of water in his hand, Koala on his shoulder, and Baby Panda waddling along behind them with a look of concern on his round face. Soon the whirr of an engine was heard, and Panchu appeared on a speeding toy mo-bike, with Pinchu riding pillion.

Mrs. Hysteria lay crumpled up on the sofa, her body lying awkwardly crooked.

“BP, you hold this mug,” Mumbo turned and told Baby Panda, “Ma and I will straighten up Aunty first”.

Baby Panda, who was trailing behind, got into a trot, which he rarely did. He looked so sweet trotting that, for a moment, everyone forgot everything else and looked at him, just as you would forget whatever it was you were doing, however important it was, if a rainbow suddenly appeared on the walls of your room.

When Baby Panda had taken hold of the mug, Mother Fen and Mumbo held Mrs. Hysteria by her feet and shoulders and placed her comfortably along the length of the four-seater sofa. Then Mother Fen took the mug from Baby Panda and began sprinkling water on Mrs. Hysteria’s face.

Meanwhile Panchu and Pinchu asked Baby Panda to put them up on the hand-rest of the long sofa, so that they could better see the goings-on.

Slowly Mrs. Hysteria opened her eyes. Mother Fen was then stooping over her, and Mrs. Hysteria’s eyes settled on hers with a glazed look She was in a daze. It took her some time to realize what had happened. When at last she remembered, she tried to rise hurriedly. While doing so her eyes fell on the tiny figures of Pinchu and Panchu staring up at her from the further end of the sofa with a great deal of curiosity on their faces. From the corners of her eyes she thought she spied the presence of others as well, and half-turning, she came face to face with Mumbo (with Koala peeking at her over his shoulder) and Baby Panda who, like Mumbo had done earlier, put his palms together in a respectful ‘Namaste’. (Mother Fen was very particular about the manners of the children).

“Namaste, Aunty,” Koala greeted Mrs. Hysteria.

“Namaste, Aunty,” piped in Panchu and Pinchu in unison. They would have wished her earlier had she not been looking so groggy.

Mrs. Hysteria stared and started. Her eyes grew big and wide, her mouth opened. She caught her breath. Then, for the second time, she passed out. Like they had done earlier, Mother Fen and Mumbo together set her right. Mother Fen said, “Children, you’d better go to the play-room. I’ll sprinkle water on her again, and when she’s okay, I’ll send her off. If I need you, I’ll call you. Thank you so much for all your help. “

The children reluctantly went away. They had so much wanted to help out, but it seemed their presence somehow made the problem worse. They felt very bad to leave their Mother all alone like that to take care of things, though they were confident she would be up to the task. You will be wondering where Father Fen was while all this was taking place. Well, Father Fen was in his own private study. He had shut out the rest of the world, and he was working. Mother Fen and all the children knew that, unless something really terrific or terrible happened or was about to happen, Father Fen was not to be disturbed. After all, wasn’t it because Father Fen worked hard that they could enjoy a beautiful house and lovely food and play with wonderful toys? He was a writer. He wrote stories for children, and children all over the world read his stories. They waited eagerly for when his next book would come out. Only Pinchu and Panchu and Koala and Mumbo and Baby Panda did not need to wait, because they were given a copy of the stories even before they were printed.

So, unlike most other people, Father Fen did not have to go to an office to work, he could work at home; but when he worked, he needed to get away and be by himself.

3 - Trouble at Fens’ Den

When Mrs. Hysteria recovered, she was not her usual talkative self. She was in a great hurry to get away, and Mrs. Fen made no attempt to make her stay back. Before she went back to her own house, Mrs. Hysteria visited five other houses on the way. In each of these places she had a lot of bad things to say about the Fens. She said Mr. and Mrs. Fen were actually black magicians who had implanted the human spirit into dolls and the young of a variety of animals, and were now trying to pass them off as their own children. She said it was very dangerous to have neighbours like the Fens. Not only were black magicians dangerous people wherever they happened to be, but animals which had been turned into humans by magic could be turned back into animals as well, and then God knew what disaster they would bring upon the people of the neighbourhood. Mrs. Hysteria was of the view that they should all get together and do something about the matter before it was too late.

What she meant, of course, was that the Fens should be forced to leave their new home. But she did not say this in so many words. She thought it would sound bad, and she never wanted to sound bad even when she had very, very bad things to say. Instead of saying, “Let’s make life hell for the Fens”, she said things like, “We are all such nice people here; it would be such a pity

if anyone from outside came here and made our lives absolutely miserable.”

Hatred is a poison we should try to keep away from at any cost. Therefore it is funny, isn’t it, that a lot of people simply love to hate? What could be the reason? Life is not perfect, and neither are we. Deep down in most of us there are heaps and heaps of anger stored up over the years because of the disappointments and failures and insults we have faced. When we have an enemy we can direct all this anger at that person, and that makes us feel better because we can take out at least some of the poison from inside us. You will now understand why, when Mrs. Hysteria went around trying to make the Fens an object of general hatred, to a great extent she succeeded. People who had not even known the Fens suddenly found out that here were people they could hate, and they didn’t want to lose out on the opportunity. But why, you may ask, did Mrs. Hysteria make an enemy of the Fens in the first place? The Fens were something she did not understand, and often when we don’t understand something we get scared of it and begin to hate it.

Two nights after Mrs. Hysteria’s visit, when all the Fens had gone to sleep, someone (or maybe there was more than one involved) threw stones over the walls of Fens’ Den and smashed a glass window. Father Fen and Mother Fen, who slept less deeply than their children, woke up at the sudden noise and rushed to the living room, from where they thought the sound had come. Seeing a few tell-tale shards of glass on the floor, they threw open a curtain to discover a jagged hole the size of a fist on the window. A few more broken pieces that had stuck on the curtain fell to the floor.

“Let’s clean up all the glass from the floor,” said Father Fen. There were tears in Mother Fen’s eyes.

“But why, Pa Fen, why?” she wanted to know. She was not asking about picking up the glass, of course, but about the attack.

“I think this might have something to do with Mrs. Hysteria,” Father Fen surmised. He had heard of her visit.

Mother Fen looked very, very worried. “If more of this kind of thing happens?!” she half-exclaimed, half-asked.

Father Fen was a sensitive mild-natured man, and he too was feeling pretty depressed. “Maybe wrong things have been said about us,” he said. “The best way to counter that would be to invite some of our neighbours for tea. Once they know what we are really like I hope the message will get around that we are all right although we are different.”

“One would think that we’ve been through this kind of thing before and so it will be no great shakes coping with it, but there are some things you never get used to, do you, Pa Fen?”

“You’re right — there are some things you never get used to, some things that always hurt … and I think that’s the way it should be, or we’d be very dead inside. I know we are different, and that we’ll have to pay a price for that; but I hope with time people get used to us here, and we never have to leave this place. After all, now we’ve built our own house.”

“Tell me one thing, Pa Fen — would you rather that we were like everyone else?”

Father Fen’s face broke into a smile. “I’ll tell you, but you say first — how about you?”

“Not for anything in the world. What would life be without Koala…? Or Panchu …? Or Mumbo …? Or Baby Panda …? Or Pinchu?” Just naming the children made them feel nice again. In their happiness they hugged each other.

“You can never tell for sure,” Father Fen reflected. “That could even have been some drunk idiot taking a pot-shot. Who’s to say our house wasn’t an accidental target?”

That brought some consolation to their minds, but neither Mother Fen nor Father Fen were quite convinced that that was actually the case. Life had taught them when to be careful, and apart from the glass, their windows had iron grilles and wooden shutters as well. From now, just to be on the safe side, they would have to close the shutters before they went to sleep, and open them up again in the morning.

Suddenly they heard the whirr of a little engine and realized it belonged to Panchu’s toy mo-bike. It took them quite by surprise. It was the last thing they expected so late at night. They looked at each other in wonder. Panchu rode into the room alone, making his vehicle halt with a little screech.

“Why Panchu, did we disturb you?” Mother Fen asked lovingly.

“What are you two doing here this time of the night?” Panchu demanded. “You should be in your beds, sleeping!”

“That’s exactly what we are going to do right now, Panchu,” said Father Fen.

That did not satisfy Panchu. “Papa, you haven’t answered my question,” he pointed out.

“But your Ma asked you a question first — you didn’t answer that,” Father Fen countered.

Panchu got off from his bike and stood with his hands on his hips, very much like a cop investigating a problem. “Question? What question?”

“What made you come here, Panchu?” Mother Fen re-framed her question.

“Suddenly I heard voices,” Panchu explained, “so I came to make a routine kyurity check.”

Mother Fen furrowed her brows, but Father Fen was quick to catch on. “He means security check”, he explained.

“Oh, so you’re making security checks these days?” Mother Fen asked, taking care not to betray a smile.

Panchu thought for a moment and then said, “I’m starting today.”

“Oh my little lion-heart!” crooned Mother Fen, bending down and picking Panchu up. She placed him on her palm so as to be able to pet him all the better.

“Lion-heart!” beamed Panchu, smiling so hard that the skin on his face was stretched to the full.

“Panchu the lion-heart!” Father Fen quipped.

Mother Fen lightly rubbed a forefinger down Panchu’s head as a gesture of affection. She could almost feel Panchu purr like a cat.

“Say Panchu,” she asked, “if you came here and found someone trying to break down the front door, what would you do?”

Panchu had the solution worked out. “I’d go and wake Mumbo up,” he declared straightaway.

“But say,” Father Fen put in, “the men had guns with them?”

Mother Fen shook her head at him in such a slight way that it could hardly be noticed, but because there was this great understanding between Mother Fen and Father Fen, he did pick up the hint: she thought such questions could frighten Panchu, and she would rather that he did not ask. But the mischief had been done, and the only way out was to quickly change the topic.

Before anyone could do that, however, Panchu was ready with his answer. “Ma told us that when we do good things, God is with us. If they have guns, we will have God. God is greater than guns.”

Mother Fen and Father Fen laughed together in delight. “Panchu’s not only a lion-heart, he’s a philosophical genius too!” Father Fen exclaimed.

“You’re using big words!” Panchu complained at once, but he was sure that the big word he was talking about meant something good, and his voice was full of expectation.

“To be philosophical is to think deeply about serious things,” Mother Fen explained.

“But you told me”, Panchu reminded her. “Then it’s YOU who’s filophical, not me.”

“Philosophical.”

“Okay, I’ll learn it in the morning. But lion-heart is okay, isn’t it?” Panchu almost blushed.

How he loved to hear that word! It made it one of the best days in his life. Father Fen had not seen this side of Panchu: he was being given credit for something, and he passed on the credit to his mother! Now how many people in the world, children or grown-up, would do that? It made him a very proud father. But Panchu hadn’t had his full say. There was a doubt in his mind:

“You’re not telling me all this because you don’t want to tell me what you were doing here in the middle of the night?”

“Now look at him!” Father Fen commented to Mother Fen, though in his mind he was thinking, ‘What a smart little fellow he is!’ Then, turning to his son, he said, “Panchu, we are your parents, but you’re talking to us like it’

s you who’s our guardian!”

Panchu took a step towards his bike. “I understand,” he said, “you don’t want to answer me.”

“Must you know everything, Panchu!” Mother Fen said with some emotion. Sometimes these little things got so difficult, it made you feel mad. Mother Fen and Father Fen never lied to their children. There were times when a lie seemed the easiest and most reasonable way of answering the many questions their children put to them, but they could never get themselves to play false with their little ones. Rather than tell them the wrong things, they preferred to try to change the subject or, if that was not possible, not to say anything at all. The problem was, when you were dealing with such bright kids, it wasn’t the easiest task in the world to switch their attention to something else; and as for not saying anything at all, it created a distance, and whenever there is a distance among people who are very close together, it makes everyone in the picture very sad.

Mother Fen thought if she could explain the matter at length to Panchu, it might help. “You’re a small child, Panchu. There are things you can’t tell a small child, see? It’s not proper for a small child to know certain things.”

Panchu turned to his father in protest. “Ma’s standing here in front of you and calling me a small child,” he complained, “and you’re not saying anything?”

Father Fen withdrew his smile and looked absolutely serious. “There’s nothing bad about being a small child, Panchu. We’ve all been small children sometime or the other — I’ve been a small child, your Ma’s been a small child … it happens to everyone, it’s good …. Now it’s your turn to be a small child, that’s all.”

“Can a small child talk like me, in proper sentences?” Panchu demanded. “Can a small child ride a mo-bike? Can a small child …”

“You and your brothers aren’t normal small children,” Father Fen explained. “You are very, very special small children, you see?”

“Then why won’t you tell me why you are here?” Panchu wanted to know.

The Fantabulous Fens

The Fantabulous Fens